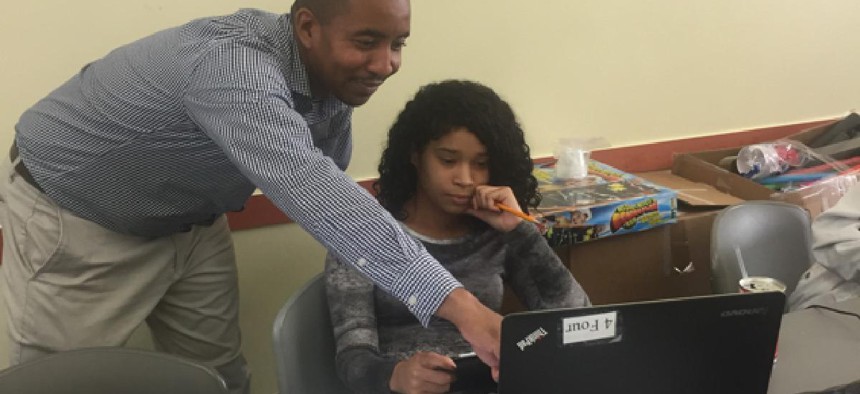

Front-Line Hero: Theory Thompson, LifeLink Program Director, Good Shepherd Services

By age 13, Theory Thompson of Castle Hill in the Bronx had buried both parents. But a scholarship from the nonprofit A Better Chance enabled him to attend a private boarding school in Philadelphia, helped stabilize his life and set him on a career trajectory to become the director of Good Shepherd Services’ LifeLink program, which gives inner-city students the tools to pursue higher education.

“Living independently with other students and focusing on academics at that early point in my life shaped my outlook,” said Thompson, who has degrees from Morehouse College, Ohio State University and Hunter College. “I wanted to make higher education available to gifted teenagers in my community.”

Founded by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd in 1857, Good Shepherd Services, which is now nonsectarian, has partnered with the New York City Department of Education since 1972 to meet the needs of underserved youth in the Bronx and Brooklyn. The organization’s budget is about $91 million and it serves more than 30,000 children, youth and families in New York City, according to its 2016 annual report.

Thompson first found his niche at LifeLink preparing high-poverty students to enroll at the City University of New York about 12 years ago. He put his mark on the college access program by creating a peer-based model using student leaders as mentors. Currently, 12 part-time student coaches and two full-time staffers – including alumnus Luis Fuentes, who serves as program coordinator for recruitment – run services that reach more than 500 students per school year. He also teaches a freshman class at Bronx Community College.

LifeLink participants range from ages 17-24. The program is broken into three phases: recruiting, mobilizing or test preparation, and retention. Their preparation for higher education begins with guidance offered through The Bridge, a six-week program designed to sharpen testing skills that uses a curriculum developed with Thompson’s oversight. After students matriculate, LifeLink’s college retention supports them with assistance navigating financial aid and keeping up with their studies.

“Our population leads complex lives and faces the challenge of balancing school with the need to earn a living,” Thompson said. Many are first-generation college attendees, undocumented immigrants or otherwise at-risk, and must contribute to the household. Thompson is struck by their resilience despite the obstacles. The program does what it can to lighten their burden. “We offer stipends, employment opportunities, even MetroCards,” he said. “High school students are eligible for travel passes, but college students pay their own way. I’ve heard of CUNY students who walked miles to get to class to save on subway fare,” Thompson said.

“I think of LifeLink as a ‘one-stop shop,’ where the participants receive ongoing support from a group of people who will cheer them on to be successful in school and beyond,” said Thompson, who considers it an honor to work with his students and looks forward to going to the office every day. He also shows great respect for his team. “He realizes that his front-line staff has insights that he may not be aware of, and takes their views into consideration,” Fuentes said.

Thompson’s work has yielded promising results: Last year about 90 percent of the 525 summer-term Bridge participants both enrolled in college and continued through the retention portion of the program. Of the fall 2015 and spring 2016 retention cohorts, 96 percent completed their first semester in college.

Sister Paulette LoMonaco, executive director of Good Shepherd Services, attributes much of this success to Thompson’s “unrelenting passion and commitment” to the program. “For so many of our LifeLink participants, Theory provides the support and mentorship they may not be getting from anyone else in their lives. He has a unique ability to inspire and empower young people,” she said.

While a LifeLink participant, Fuentes had a passion for history and enjoyed helping classmates prepare for the history and government Regents exam. Yet college and paying for school books did not seem possible until he met Thompson.

“Theory is my blueprint,” said Fuentes, a graduate of New York University, who became the first member of his family to earn a college degree. Fuentes still marvels that he has maintained this path. Now, even his mother has matriculated at CUNY with the goal of becoming a social worker.

“Theory comes from our neighborhood and overcame a lot of adversity,” Fuentes said. “He polished me and helped me pursue my passion, for which I am eternally indebted. I wouldn’t be here if not for him.”