Nonprofits

Nonprofit delivers books – and access to information – to those in prison

How a couple of public defenders and their seven-year-old organization joined other groups in sending thousands of titles to incarcerated individuals.

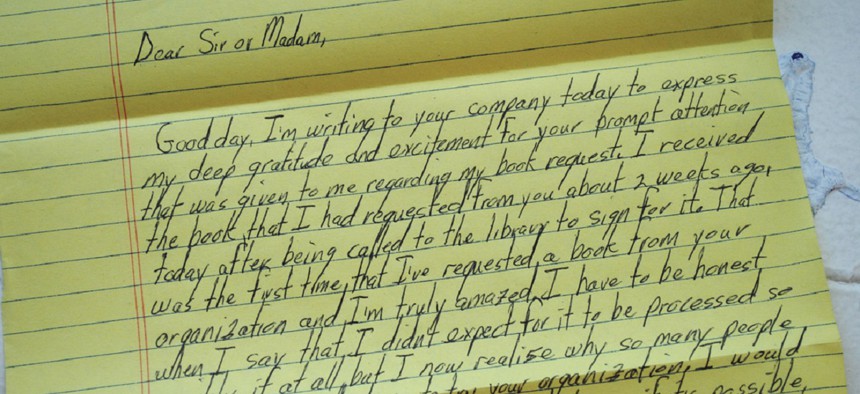

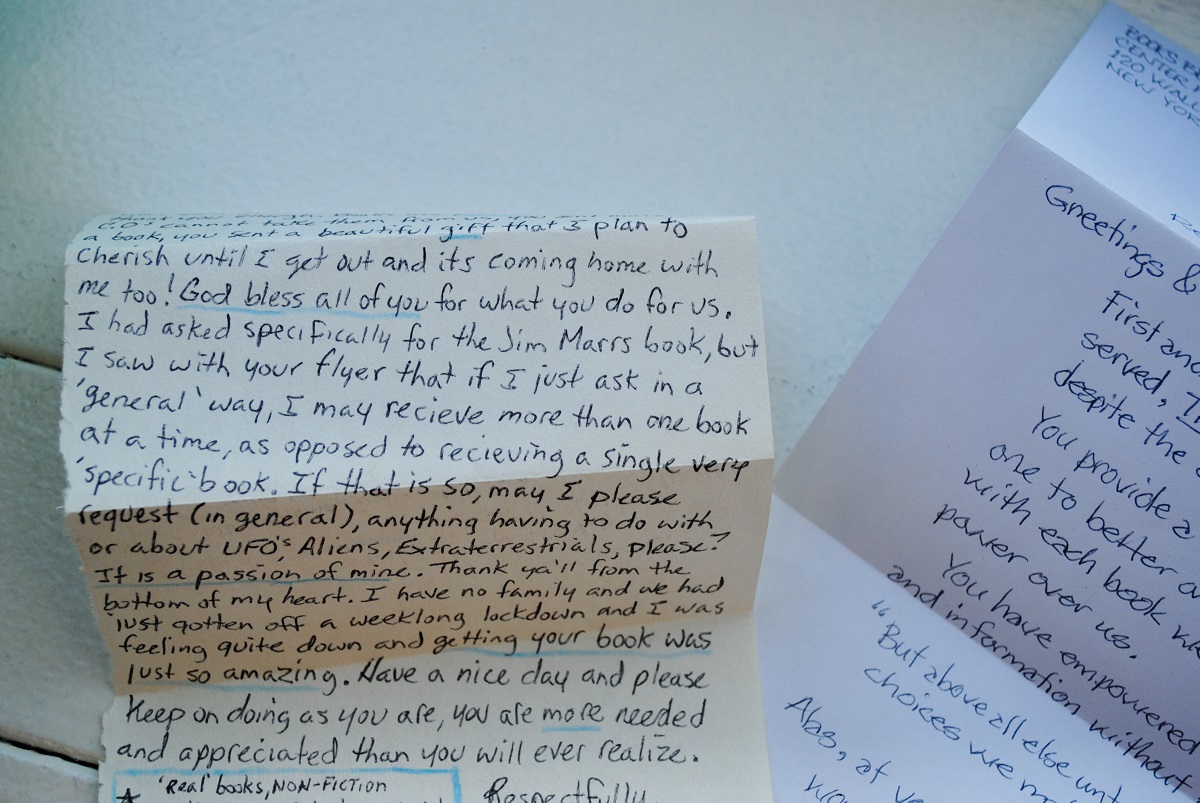

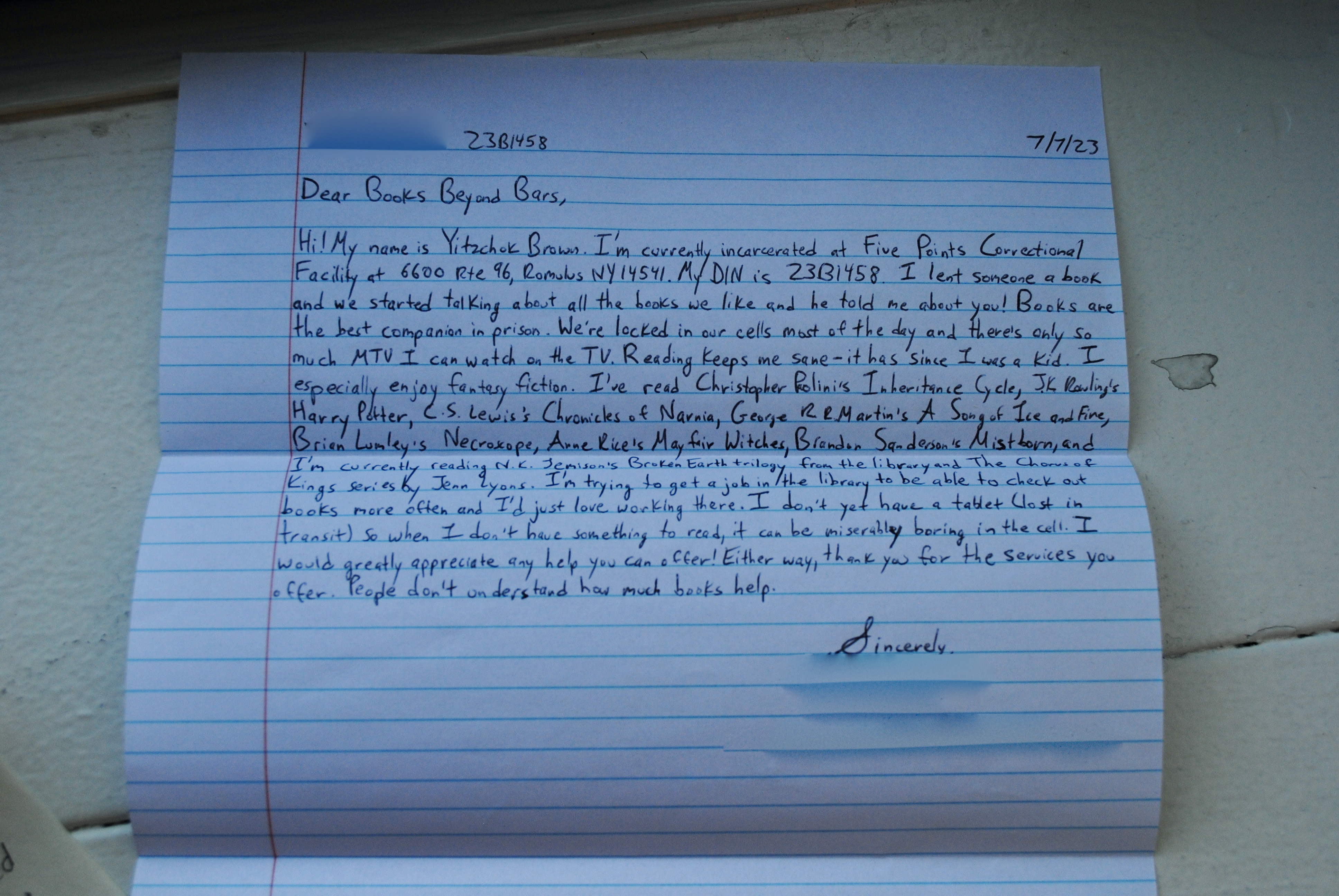

An incarcerated person's letter to Books Beyond Bars. Photo by Hannah Berman

At the Center for Appellate Litigation, a nonprofit, public defense firm, things don’t move so quickly.

The New York City based CAL’s clients have already been convicted of crimes and sentenced to serve time in prison. From the court’s perspective, there’s no urgency to hear their cases again. That means that the appeals process for criminal defendants is very much an uphill climb – a long, tedious struggle against an unsympathetic system.

When meeting with clients who are isolated in prison with a long road of appeals ahead, CAL public defenders Ben Schatz and Molly Schindler felt an urge to offer up a more immediate, tangible type of aid – something to make their clients’ everyday existence less lonely.

“It sort of started with me and my officemates saying, ‘Well, what can I do for you today?’” Schatz said. “‘What’s something that we can offer up to you as a token of our commitment to your case – to show you that we are serious about this, that we care about you as a human being, and that we want to help you escape, to the extent we can, the really harsh reality that you're going through?’”

Their clients’ answers were clear. They wanted books.

As a result, in 2016 Schatz and Schindler co-founded Books Beyond Bars, a nonprofit with a radically simple mission: Incarcerated people should have access to information, too.

“We're not here to take a position on what they should be reading, we're not here to educate, we're not here to impose our views on anyone,” Schatz said. “Access to information is a right that is taken for granted by pretty much everyone with a smartphone, and this is a group of people for whom that right is just as important, and so severely limited.”

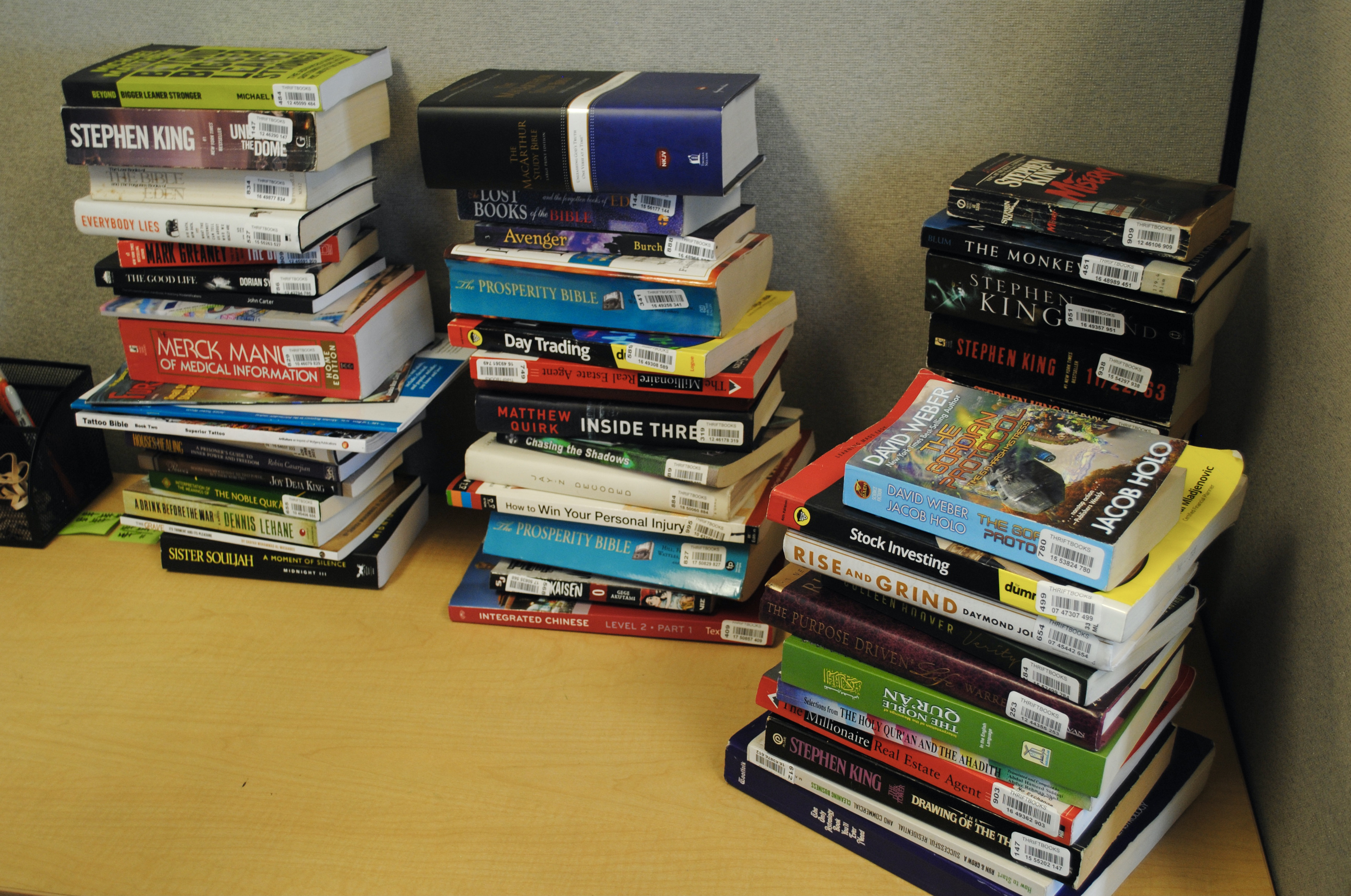

Books Beyond Bars has a basic, three-step operation: the organization receives requests for books via letters from inmates, buys the requested books and sends them back out. It’s that easy. At first, BBB served only the clients of the Center for Appellate Litigation; but soon enough word got around, and now the organization regularly sends thousands of books per year to over 50 state-run facilities in New York.

Alexandra Schoenborn, BBB’s new Program Coordinator, has been volunteering with the organization as a fulfillment intern since March.

Shoenborn said she was drawn to join BBB because it’s a project where immediate action returns immediate results. “There are lots of injustices that we aren't necessarily making as much progress on as we'd like to, [but] we can help in this really small way,” she said.

The only possible hiccup in the BBB equation is the intermediary: the prisons themselves. Package examiners in prisons need to approve each book that gets sent, a potentially contentious issue in a world of book bans. Even though New York prisons are less strict than other states, books regularly don’t make the cut, and it’s not always clear why.

Schoenborn said, “We do our best — even if we're not ideologically aligned, we do have to work with them, and we definitely think it's also in their best interest to have the inmates reading and pursuing their various interests through the books that we send.” Schoenborn keeps a list of prison literature guidelines tacked up in her office to avoid sending something an inmate won’t be able to receive.

The organization is similar to other books to prisons programs, like Books Through Bars. Schatz knows that, and is happy that there are other organizations doing the same work.

He said, “I mean, we didn't invent this. There's no downside to having more and more of these [books to prisoners programs] because the hunger for literature in prisons is insatiable.”

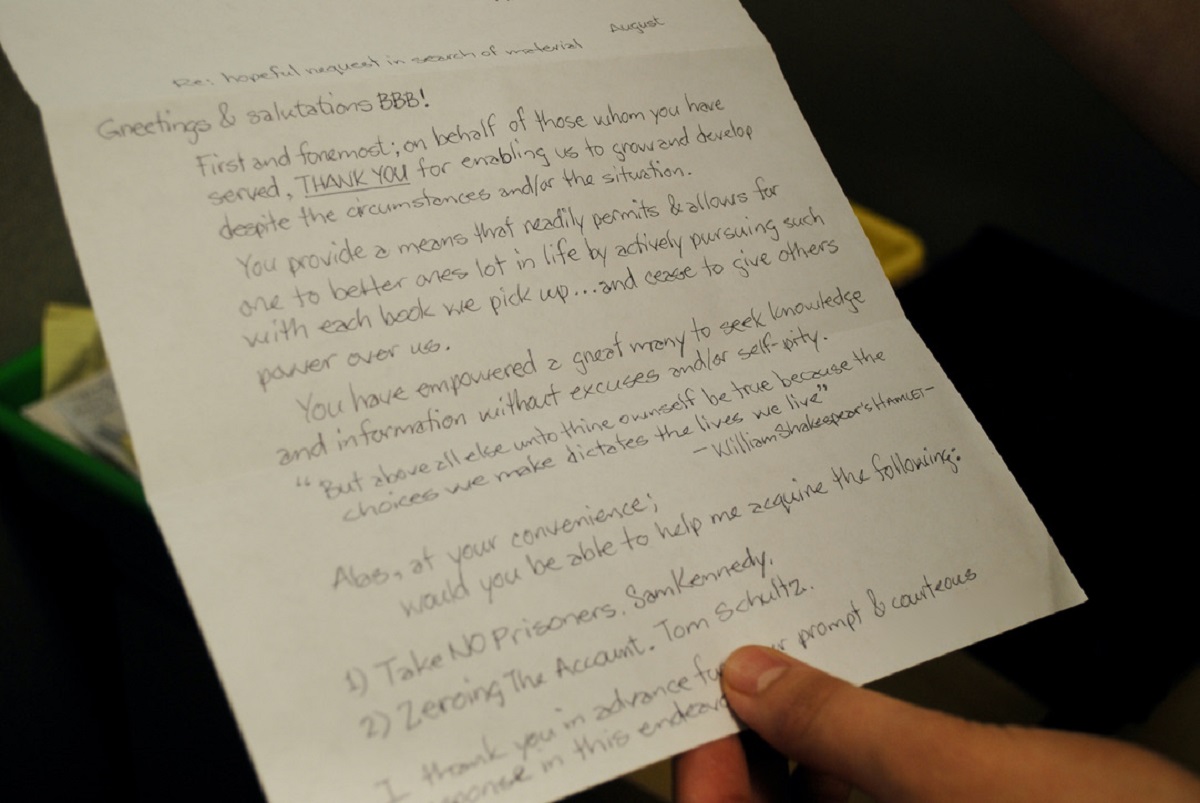

The proof of this hunger is in the letters that readers send back to the BBB office.

“I have been incarcerated since I was 15 years old. I am currently 25 years old,” one book recipient writes. “I became interested in reading when I enrolled in a college program at 18 and received my associates at 20. Since then this is a list [of] books that have been on my wish list but because of lack of support I have not been able to achieve them,” with ten requests attached.

"Books are the best companion in prison. We’re locked in our cells most of the day and there’s only so much MTV I can watch. Reading keeps me sane – it has since I was a kid,” wrote another book recipient. One incarcerated person noted the saying, “Your (sic) a prisoner in your own mind, only if you allow yourself to be,” and added, “When I open a good book it take’s me to another place."

The letters also acknowledge that the BBB formula works. “BBB provides such an outlet; that help educate the mind, and helping the prisoners’ imagination escape the reality of their enslavement, by reading books which provides – an outlet of freedom,” said one incarcerated individual.

Having a book in hand obviously doesn’t solve the real problems at the heart of incarceration; but when those core issues take years to solve, BBB testifies to the fact that it’s still meaningful to provide moments of joy.

“I have no family and we had just gotten off a weeklong lockdown and I was feeling quite down and getting your book was just so amazing,” writes another book recipient. “Have a nice day and please keep on doing as you are, you are more needed and appreciated than you will ever realize.”