New York City

Will NYC’s nonprofit procurement process ever be functional?

New York City spends 35% of its procurement budget on nonprofit contractors, but payment delays continue to vex vendors.

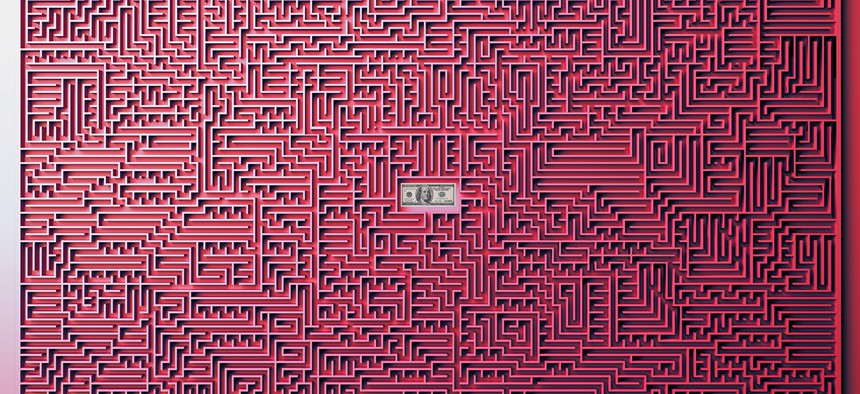

For nonprofits, getting paid can feel like a monumental task. Credit: Andrew Horton (LdF/Elena Frolova/Getty Images)

Sourcing, contracting and paying external vendors for goods and services – all of which fall under the big umbrella of procurement – are a big part of New York City government. The city spends about 35% of its total budget on goods and services procured from third parties of which the largest share, about $9.9 billion in fiscal year 2023, is for human services from nonprofit organizations.

Despite this largesse, nonprofit vendors regularly complain that the city’s procurement system is complex, antiquated and creates lengthy payment delays that are costly, sometimes even fatal, to organizations waiting for their money.

Origin story

“The city’s contracting system is fragmented and chaotic. The contracting operations are awash in a sea of paper, plagued by inordinate delays, and clouded by unclear and inconsistent rules and procedures which slow city business to a crawl. Over the past several years, scattered attempts at reform have been made. … But New York City’s contracting operations are too big and too complex to be reformed piecemeal.”

This might seem like a recent characterization, but it was written in 1989 as part of a broader report, “A Ship Without A Captain: The Contracting Process In New York City,” issued by the state Commission on Government Integrity in response to a series of scandals related to New York City procurement. At the center of the scandal was bribery and extortion involving contracts awarded by the city Parking Violations Bureau that involved Queens Borough President Donald Manes, Bronx Democratic Party Chair Stanley Friedman, Queens lawyer Michael Dowd and more than a dozen city officials – leading to many resignations. In fact, the core elements of our current procurement system were put in place at that time – mostly through the 1989 City Charter revisions – in response to these scandals: procurement as an administrative function under the full control of the mayor, Vendex, the Procurement Policy Board and the roles of the oversight agencies. Within a year, the newly created board had built upon this core to issue hundreds of pages of detailed rules and regulations, most of which we live with today.

The origin story is important since any procurement system has three primary goals – prevent corruption (or its appearance), efficiency and fairness to vendors – which can be at odds with one another. One school of thought, common among grizzled realists who were there at the time, is that New York City will never be able to appropriately balance these goals since its procurement system started as an overreaction to scandal, mayors are loathe to simplify processes for fear of corruption (or its appearance) and any new requirements will tend to be in addition to, rather in place of, what has gone before. Frank Anechiarico, who worked with the state Organized Crime Task Force in the late 1980’s and later did research on the procurement system with his colleague James Jacobs, said, “In the wake of the scandals, there was no balance. It was a mad rush to cover everybody’s butt. Even many years later we heard a common refrain: ‘It’s far more important to look honest and diligent than to get anything done.’”

Ironically, while for-profit companies were the locus of corruption in the 1980s, they seldom complain about procurement since most have three easy ways to immunize themselves from any dysfunction in the system: avoid doing business with the city; price the hassle into their bids; refuse to begin work until all the paperwork is done. None of these strategies are available to nonprofits providing human services under city contracts. For many human services organizations, such as homeless shelters or summer youth programs, New York City government is the sole buyer or payer, so nonprofits cannot simply refuse to work with the city. They cannot “price in” the procurement hassle since human service contracts with nonprofits are cost-based with no profit allowed and “hassle” is not a reimbursable expense. They cannot refuse to work prior to the paperwork being done given the human cost involved in withholding services from often vulnerable people – not to mention that a refusal to start would likely be met with the nonrenewal, perhaps even nonregistration, of the contract. So the bitter irony is that nonprofits bear the brunt of a system created in response to scandals in which they played no part.

Incremental progress

However, despite the skepticism of the realists, there has been meaningful progress in the procurement system starting, unsurprisingly, under Mayor Mike Bloomberg, who had a rare interest in the plumbing of government as well as an engineer’s focus on efficiency. As Joel Copperman, who led the Mayor’s Office of Contracts from 1986-1990, said, “The system was too complicated for agency and program staff to understand let alone navigate. The only mayor who really understood large-scale systems and the need for change was Bloomberg.”

The Bloomberg administration started the first initiative to modernize the infrastructure, which resulted in HHS Accelerator in 2013 and laid the groundwork for PASSPort, which was launched in 2017. While these infrastructure improvements did nothing, on their own, to change the rules, they dramatically decreased the burden of following them. Nonprofits used to submit volumes of documents, printed in triplicate, signed in blue ink and delivered – sometimes by vans rented for the purpose – to each agency. Happily, those days are gone and the Bill de Blasio and Eric Adams administrations have continued to develop these systems including, most recently, making the data available through PASSPort Public, which together with Checkbook NYC, has greatly advanced transparency by providing a reasonably good window into procurement with the potential to disclose more information in the future.

The Bloomberg administration also started the process of standardizing human services procurement across city agencies. After two years, a standardized human services contract was released in 2011, which provided basic definitions, the terms of agreement, fiscal procedures, information related to recordkeeping, deliverables, audits, reports as well as personnel practices and records. The standardized contract eliminated the need for providers to negotiate unique terms and conditions with each government agency for every contract. Moreover, the contract was the beginning of a standardization process that continued under de Blasio’s Nonprofit Resiliency Committee with the development of a Health and Human Services cost policies and procedures manual, which, for the first time, defined indirect costs and made clear that they would have no impact on proposal evaluation by agencies.

The Nonprofit Resiliency Committee also led to the adoption in fiscal year 2017 of an automatic advance payment of 25% of the annual contract budget when a human services contract gets registered. From the perspective of nonprofits, this advance was probably the greatest single change to procurement in the past decade. No longer would nonprofits have to wait twice: first for a contract to be registered and then for the money to start flowing. For 31% of new, nondiscretionary fiscal year 2023 contracts that were registered late, the advance fully covered the expenses incurred through the registration date.

Adams’ plans

While it might be heresy in some nonprofit circles, the Adams administration’s early focus on procurement and its achievements to date have been impressive, despite continued pockets of dysfunction, which have been nearly fatal to the nonprofits involved – or fatal in the case of Sheltering Arms. It was a pleasant surprise that even before taking office, Adams, then the mayor-elect, and Comptroller-elect Brad Lander announced a “A Better Contract for New York: A Joint Task Force to Get Nonprofits Paid On Time,” which later developed a reasonable set of 19 recommendations with support from consulting firm Bennett Midland. In a separate workstream, a consulting team from McKinsey & Co. explored longer-term changes that might improve procurement but would require changes to state law and the Procurement Policy Board. The mayor also followed a de Blasio-era recommendation to turn the Nonprofit Resiliency Committee into the Mayor’s Office of Nonprofit Services and appointed Karen Ford as its inaugural executive director.

Even skeptics unmoved by task forces, press releases and unproven mayoral offices must acknowledge two recent rule changes that should make a real difference in the future: an allowance clause that preapproves amendments to human services contracts provided that they are within 25% of the original amount and preapproval for up to two renewals of discretionary items. Amendments and discretionary items represented about 80% of the total human services contracts registered in fiscal years 2022 and 2023, so these two changes could reduce the procurement burden by close to one-third. Skeptics should also note that PASSPort Public showed that 36% of new, nondiscretionary fiscal year 2024 human contracts with 7/1 start dates were registered on time and 93% had been registered by Sept. 18, a dramatic improvement over the similar figures for fiscal year 2023, which were 28% and 53%, respectively.

Despite this progress, the need for whack-a-mole projects on pockets of dysfunction – rapid response teams for the Department of Education’s early childhood education contracts, the movement of contracts from the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice to the Department of Youth and Community Development, and the “clear the backlog initiative” – remind us that while the procurement rules and infrastructure have greatly improved, the actual results are still largely dependent on the people involved. The consensus view is that de Blasio had very little interest in the human side of procurement. By contrast, the people now in important positions – First Deputy Mayor Sheena Wright, Mayor’s Office of Contract Services Director Lisa Flores and Lander – have deep experience in procurement and understand its importance to nonprofits. However, these leaders are just the tip of the iceberg, since there are thousands of people involved in procurement inside New York City government with a wide range of motivations, skills and experiences.

The intensity with which these people are managed matters a lot, as shown by the positive results of the one-off exercises and by the consistent differences among the performance of different agencies. A Mayor’s Office of Contract Services white paper from November 2021, said: “Procurement organizations report greater effectiveness when they report directly to agency executive leadership. … It is recommended for there to be a high level of coordination and accountability between the (agency chief contracting officer), legal and fiscal teams. If there is not an alignment between the players, the planning of procurements (specifically timelines) suffers.” In simpler language: Some agency leaders care about procurement, some don’t. Some teams are organized; some aren’t.

The good news is that PASSPort and other systems will soon be able to generate much more detailed information about cycle times, bottlenecks and perhaps even specific people who are consistently failing to get stuff done. This will create the potential for more active management; whether it is realized will depend on political will.

Nonprofits also need to acknowledge their people issues too. The inconvenient truth is that some nonprofits are consistently better at navigating the procurement system than others. Kevin Quist, one of the founders of BTQ, an outsourcer of finance for nonprofits that is probably the single largest manager of human services contracts with the city, said, “Superior results come down to getting payroll and costs center allocations right, understanding the differences in how different agencies operate and maintaining a well-staffed fiscal department with limited turnover.”

The way forward

The Joint Task Force to Get Nonprofits Paid on Time has a lot of objectives, but there are a few things that would be good to accomplish over the next year. The first would be keeping retroactivity under control without the need for one-off initiatives as well as having the amendment allowance and discretionary preapproval items lead to improved performance in the fiscal year 2025 results. Another would be fully utilizing the Returnable Grant Fund, and when it proves insufficient in size, then increasing it further. The city should also enter into master contracts with some of its longest-standing and largest human services vendors. And finally, recognizing that human services are different from other types of procurement, some human service contracts are treated as grants through an enabling revision to state General Municipal Law 103 and other governing regulations.

But far more important than all this is people. None of these things will amount to much unless the Adams administration actively manages the people involved in procurement to instill a culture where procurement results matter. For many people, this change will be jarring since despite some important progress in rules and infrastructure, seemingly nobody involved with procurement faced real consequences for failing to get stuff done during the de Blasio administration. And it will be more difficult for some agencies than others, in particular the Department of Education, which seems to be a procurement island all to itself having only been under mayoral control for 21 years.

Pruning back

In her recent book, “Recoding America,” Jennifer Pahlka describes government systems as representing “decades of competing interests, power struggles, creative work-arounds and make-dos that are opportune at the time but unmanageable in the long run.” Nevertheless, the past decade showed that progress has been possible. It’s finally time to leave the 1980s behind, build upon a decade of incremental improvements in rules and infrastructure, and make sure that the people involved with procurement are focused on getting stuff done. Nonprofits and their advocates should acknowledge the progress to date, but since backsliding is an ever-present risk, they must push for more and never be shy to call out pockets of dysfunction. Left unaddressed, those problems can quickly create existential threats to nonprofits waiting to get paid and impose unfair burdens on their staff and the people they serve. As Michelle Jackson, the executive director of the Human Services Council, said, “Procurement is like a garden which can be improved but will run wild if not tended for too long.” In these tough times, the city needs its nonprofit partners more than ever.

John MacIntosh is the managing partner of SeaChange Capital Partners, which provides grants, loans, analysis, and advice to help nonprofits navigate complex challenges including mergers, partnerships, financings, restructurings and dissolutions.

NEXT STORY: What it takes to get a disorder recognized